Ruby Frost

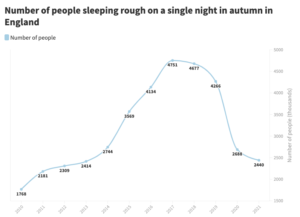

There’s no escaping the fact that Britain is on the brink of experiencing a homelessness crisis. In February, the government released the ‘autumn snapshot’ of homelessness in England. These statistics are based on the number of people spotted sleeping rough on a single night in autumn in England.

What does the data say?

The most recent snapshot, from autumn 2021, shows that the number of people sleeping rough in 2021 has decreased by just under 250 people, from 2680 in 2020 to 2440 in 2021.

Data source: Homeless Link, data presented by Ruby Frost via Flourish.

For an interactive version of this graph, please click here.

We see a sharp decline in the number of rough sleepers between 2018 and 2019, which coincides with the Government’s launch of the Rough Sleeping Initiative. In 2021, it was announced a further £203 million funding would be awarded to councils and charities to help get the nation’s rough sleepers off the streets.

“many leading homelessness charities are predicting that we are on the verge of a homelessness crisis.”

From the data alone, many would think that homelessness in England is decreasing. However, these statistics fail to explain the real picture, and many leading homelessness charities are predicting that we are on the verge of a homelessness crisis.

Osama Bhutta, Director of Campaigns at Shelter, said: “These figures show the race to end rough sleeping has started but it is far from over. The extra provision of emergency accommodation was working last autumn to put a roof over people’s heads.”

However, only a margin of homeless people were put up in temporary accommodation, and deaths of those without a permanent address skyrocketed during the coronavirus pandemic. So, as the living crisis becomes more severe and more people begin sleeping rough for the first time, why is homelessness in England still so misunderstood?

Why is the data misleading?

To start with, there is no national figure that is able to depict exactly how many people are sleeping rough because many homeless people do not show up in official statistics at all.

This is because homelessness, also known as core homelessness, includes people who are rough sleeping, as well as people living in sheds, garages and other unconventional buildings, sofa surfing, hostels, and unsuitable temporary accommodation. Therefore, the national statistics–which are based on the number of people spotted sleeping rough on the streets on one night in autumn–are unable to accurately include those who are sleeping rough, but are hidden away from the streets.

Hidden homelessness is a term used to describe people who do not have a permanent home, but sometimes find a place to stay, such as with friends for the night. This makes it especially difficult to know exactly how many people are homeless because many may not consider themselves to be, and therefore do not seek support from available services. This makes it difficult for initiatives, such as the rough sleeping initiative, to truly help all those who require permanent housing.

Furthermore, as Bhutta said, COVID-19 measures saw lots of temporary accommodation and a sense of urgency to provide shelter for those who were living on the streets, which could explain why we have seen a decrease in those counted in the autumn snapshot.

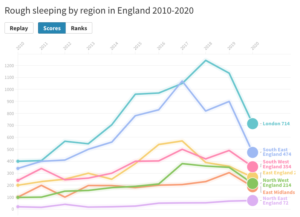

Data source: Homeless Link, data presented by Ruby Frost via Flourish.

For an interactive version of this graph, please click here.

The graph above shows that every region in England has seen an increase in homelessness since 2010, but only one region (the North East of England) saw an increase in rough sleeping in 2020.

Every region bases their statistics on a snapshot of rough sleeping on a single night but homelessness charity, Crisis, has estimated that as many as 62% of single homeless people do not show up on official figures and run the risk of slipping through the cracks. They carry out their own annual study which, on any given night, suggests that tens of thousands of families and individuals are experiencing the worst forms of homelesses across Great Britain.

“the causes of homeless are misunderstood”

Another problem is that the causes of homeless are misunderstood, and this in turn is affecting how England can control their levels of homelessness.

What can we do now?

Hariye Beydilli, 23, from Bristol, volunteers for a homelessness charity called Blonde Street Angel Team. They focus on the importance of providing the products and services that homeless people need, including food, clothes, and tents. She also says that the team makes effort to have meaningful conversations with the homeless people that they meet on the streets, as they often can be overlooked and ignored by wider society.

She explains: “There does seem to be a pattern of people believing homelessness to be a fault of the individual or a result of drugs, rather than considering the wider structure and oppression which resulted in them enduring and experiencing homelessness. The individuals I work with are all motivated and hopeful about a better and stable life in the future.”

Beydilli explained that one thing that surprised her from her volunteering experience is the problematic homeless hostels.

She explained: “While on the surface homeless hostels seem perfect to bridge the gap for homeless people and provide them with a permanent address, in reality these hostels have no rehabilitative support.”

Beydilli has spoken to some people who revealed that they actively avoid residing in these hostels, as they believe that they have a better chance to recover from their addictions living on the streets by themselves.

When discussing the data, Beydilli echoed Bhutta’s thoughts. While it looks promising, the hard work is far from over and the statistics fail to give an explanation of the wider issues.

She also discussed the Government’s Rough Sleeping Initiative, stating: “While I am reassured that the government is increasing funding, I think it ignores the wider issues and again follows the narrative that homelessness is the fault of the individual. It is the same as attempting to put a plaster on a burst artery, it doesn’t stop the problem. I think the best approach is to consider the wider structural issue and put greater focus on preventative measures, whilst also trying to help, not forgetting those who are still experiencing homelessness now.”

Preventative methods are also backed by the UK population. When 2,180 adults were surveyed for an Ipsos Mori poll, 61% supported investing money in preventing homelessness rather than paying to deal with the issue when it reaches crisis stage.

“there is still so much more work to be done.”

While there are measures in place to help the nation’s rough sleepers, and there is evidence of support services and help (such as by the Blonde Angel Street Team), there is still a misunderstanding when it comes to England’s homeless. The data seems to underestimate just how many people are homeless, and–as both Bhutta and Beydilli said–there is still so much more work to be done.

More information can be found here:

Featured image courtesy of Art Tower on Pixabay. No changes were made to this image. Image license can be found here.