British houses consume a majority of natural gas across all of the consuming sectors and contribute highly to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. When compared to France, UK gas consumption was up almost 30 per cent. The United Kingdom is one of many countries with an ambition to have legally binding net-zero emission by 2050 – or earlier. Since it is unlikely that all old British buildings will be replaced by new ones, which are going to be obliged to install low-carbon heating systems from 2025, is there something else to do in the meantime, except relying on financial support from Green House Grant?

Although the UK is a world leader in decarbonisation and the country is heading fast towards its commitments when it comes to carbon emissions, the British housing sector still falls behind with its gas burners, single-glazed windows, and poor insulation.

Between the years 2009 and 2019, the coal production in the UK decreased by a remarkable 87 per cent and instead of coal (and oil), it is natural gas that is often considered for a better solution since it emits less CO2 when burned for fuel. Although terming it “natural” may evoke calm, a transition from coal and oil to gas is not a solution – we might have moved a little further from a disaster, but we still stand on fossil fuels’ property.

Why should natural gas raise concerns?

When burning for energy, natural gas releases CO2, but also methane, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and other compounds. Often considered the “other greenhouse gas”, methane is actually the second most significant after the carbon dioxide. Around 60 per cent of methane is emitted into the atmosphere by people, while they grow rice, gain fossil fuels, burn landfills and biomass, or breed ruminants. The rest of it comes from natural sources like wetlands or termites. Although methane lives for a much shorter time in the atmosphere, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), it represents 80 times more potent GHG than carbon dioxide when it comes to trapping heat. The methane makes up a majority of natural gas compound, the fossil fuel, which boasts itself with possibly misleading name considering its major harmful impacts.

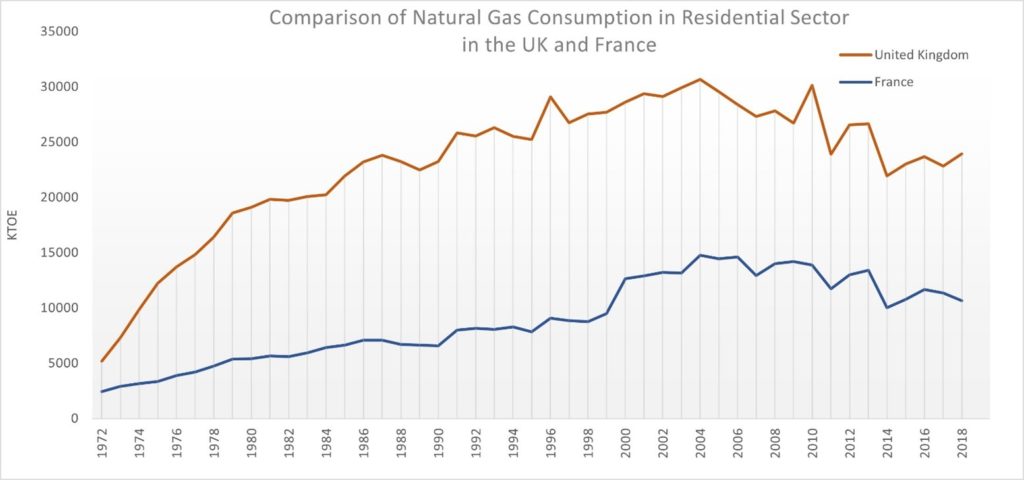

“French buildings consumed even less than half the amount of natural gas than houses in the UK in 2018.”

In the UK, natural gas is used across six monitored sectors from which is arguably the residential sector the most consuming one since nineties. According to the IEA statistics, housing is responsible for almost three times higher gas consumption than industry and almost four times higher than commercial and public services sector.

In comparison to France, a country with almost the exact same population, the final gas consumption in the UK is approximately 27 per cent higher. The residential sector in France also represents the most consuming one; however, French buildings consumed even less than half the amount of natural gas than houses in the UK in 2018. France ended the gas production in 2014 and, therefore, it is fully dependent on its import from other producers. Since the country‘s main energy source is nuclear power, its industry and infrastructure is naturally trying to adapt mostly to electrification and low-carbon fuels.

A transition roadmap to a carbon-free future

Last year, the Prime Minister announced a new emissions target, which should lead the UK to net-zero by 2050. The aim is to reduce GHG emissions at least by 68 per cent by the end of the decade when compared to 1990 levels. Research carried out by Element Energy, commissioned by the Climate Change Committee (CCC), developed five pathways to the full decarbonisation of heating in the UK homes by 2050. A balanced pathway would cut today’s emissions from homes in half by 2035 and a full decarbonisation could be achieved with an average net investment of less than £10,000 per home. Offered scenarios in the research count with low-carbon heating systems such as low-carbon district heat, heat pumps, and direct electric heating for every home.

“A balanced pathway would cut today’s emissions from homes in half by 2035…”

Another way to get closer to net-zero emissions economy might be switching natural gas for hydrogen. A recent study conducted by Imperial College London, published in Energy & Environmental Science journal last year, assesses national heating network and offers a hydrogen transition roadmap. The paper shows that transition would be rather expensive, although it also suggests additional options like subsidies implementation and policy innovation in order to achieve a carbon neutrality.

“According to the study, smart heat technologies have big potential to reduce household emissions.”

There are already studies anticipating heat electrification in UK homes. For example, in last August a paper by Energy Futures Lab was published, exploring the advantages of smart, flexible, low-carbon electric heating. According to the study, smart heat technologies have big potential to reduce household emissions. A development within a long neglected residential sector is certainly on the rise, and alongside regulations and legislations such as carbon taxation, the EU’s large combustion plants directive or subsidies for renewables contribute to the UK’s emission-free future. However, there are certain concerns about the commitment to act, as the £1.5 billion green homes voucher scheme was scrapped in March and replaced with a £300 million separate green housing scheme.

“However, there are certain concerns about the commitment to act…”

The UK government unveiled a £1.5 billion green homes grant last year, under which the homeowners should receive financial support for new insulation, heat pumps, and other low-carbon improvements. Despite high levels of interest, more than £1 billion from the scheme remained unspent and many applicants made complaints about not getting approvals for their payment.

What can be done towards sustainable equipment for buildings?

Industry and investor decisions could be directed towards sustainable development for items such as building equipment and governments need to set long-term goals. In its report on heating from last year, IEA recommends removing subsidies for fossil fuels and offering public subsidies for clean-energy technologies instead.

To support sustainable heating, there will be a requirement for new homes, built after 2025, to have a low carbon heating system. However, as stated in CCC report from 2020, since the Climate Change Act was passed, almost two million homes have been built and this change is long overdue.

Natural gas, like other greenhouse gases, plays an important role on the way to net-zero targets but replacing the “very bad” with the “less bad” does not seem to fit in with a sustainable development scenario.

Featured image courtesy of @Emilian Robert Vicol on . Image license found here. No changes were made to this image.