Seven Standen

Content warning: calories, diet culture, eating disorders.

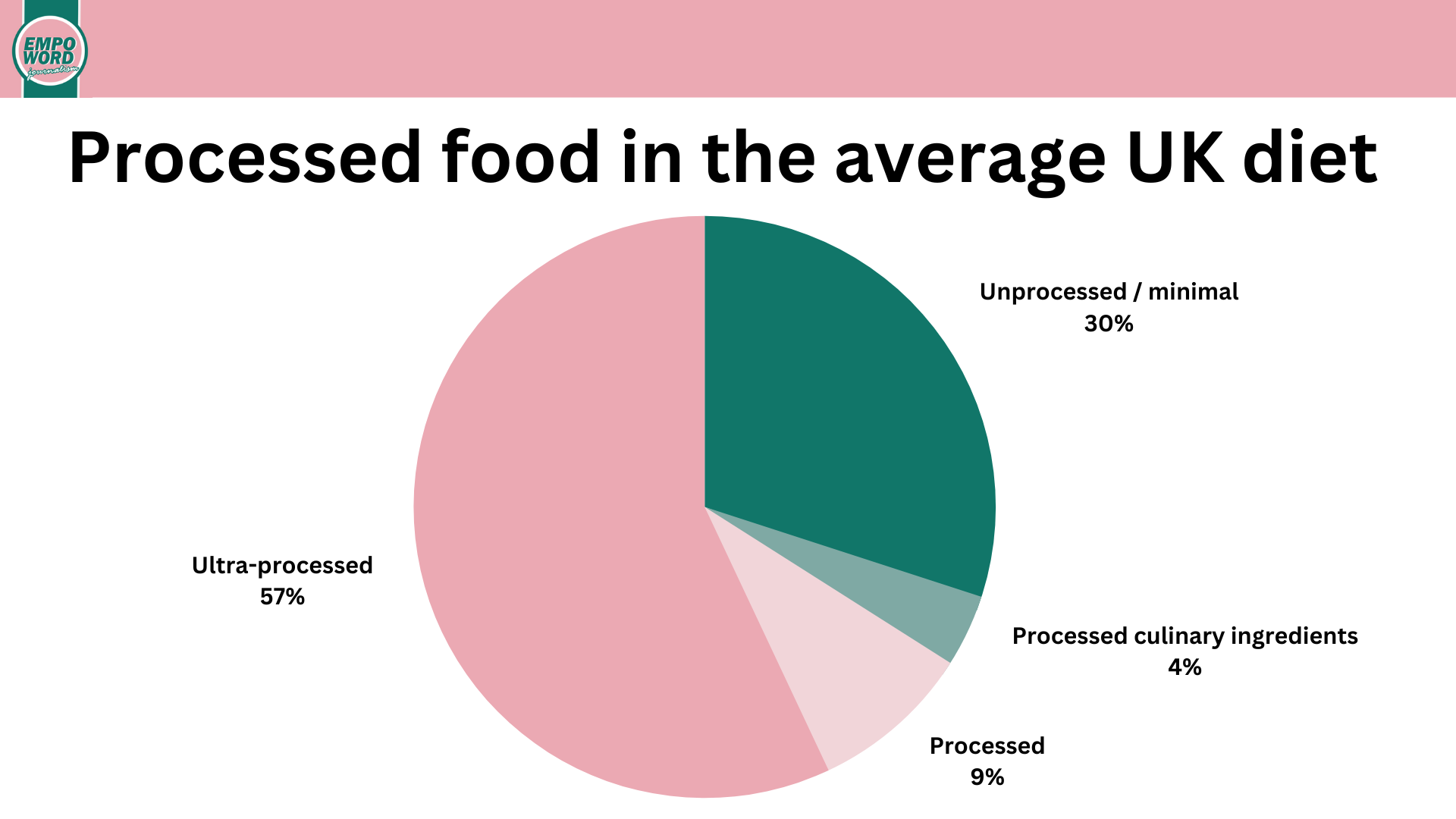

More than half the food the average person consumes is ultra-processed food (UPF). This shocking statistic, uncovered by a 2018 study, has launched a recent panic in the UK media over what we’re eating. But what on earth is UPF? How has everyone, from our grandparents to our pets, been consuming it for years without our knowledge? And is it actually something to worry about?

Most of us have been consuming UPF since we were born, yet we didn’t have a name for it until recently. The UPF phenomenon, sometimes referred to as “food that isn’t food”, can be traced roughly back to 1980s consumerism. Although it had existed for decades previously, Ultra-Processed Food didn’t become a big part (or even the main part) of our diets until then. Today, virtually everything we eat is classified as UPF.

But, before you panic about the consumption of this mysterious food, it’s worth explaining what ultra-processed food is and why so many people are worried about it.

What is Ultra-Processed Food?

Ultra-processed food (UPF) is a category of food and drink that has undergone extreme levels of processing. These foods are highly altered and typically contain a lot of added salt, sugar, fat, and industrial chemical additives.

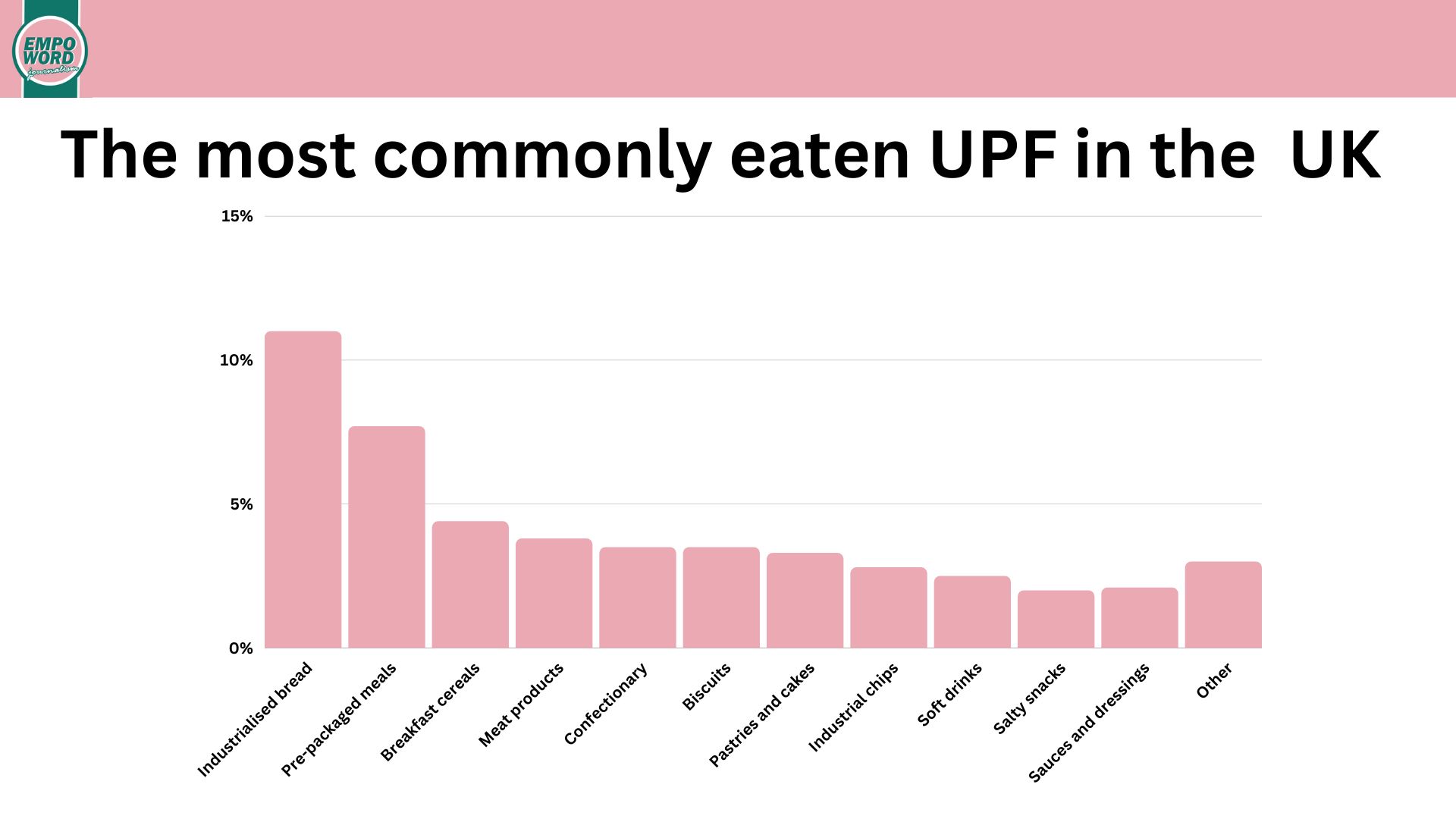

Most people immediately think of ‘junk food’ (such as chocolate, sweets, and crisps) when they imagine what UPF is. It’s true that confectionary, biscuits, cakes, and chips are all kinds of UPF. However, plenty of the normal things we eat and drink on a daily basis are also categorised as ultra-processed.

Some of these foods are obvious, such as pre-packaged meals. But you might be surprised to find out how much UPF you actually eat without knowing. In the UK, the most commonly eaten forms of UPF are industrialised bread, breakfast cereals, and reconstituted meat products.

Isn’t all food processed?

It might not be surprising to learn that processed food is everywhere. Anyone who regularly cooks or bakes knows that a certain level of processing is required to make most food unless it’s raw fruit and veg. You can’t make the most basic bread without making flour from wheat and combining it with water.

However, there are different levels of processing involved when it comes to food. The NOVA food classification system, developed by nutritionist Carlos Monteiro, divides food into four categories:

Unprocessed and minimally processed

This includes fruit, vegetables, nuts, seeds, grains, beans, pulses and natural animal products (such as eggs, fish, milk, and unprocessed meat). Minimal processing means these foods may have been dried, crushed, roasted, frozen, boiled or pasteurised – but, most importantly, they contain no added ingredients.

Processed culinary ingredients

This includes oils and fats such as butter, vinegar, sugars, and salt. All of these foods aren’t intended to be eaten alone (making them different from the first category) but instead to make other things.

Processed

This includes cured whole meats, cheeses, fresh bread, bacon, salted or sugared nuts, tinned fruit in syrup, beer and wine. Unlike the previous categories, these are foods that don’t exist alone and, instead, are a combination of other kinds of foods. These foods are processed to extend their life or to enhance their taste.

Ultra-processed

As you might expect, this category includes ice cream, soft drinks, cakes, pastries, and crisps. Supermarket pizzas, chicken nuggets, and ready meals may not be immediately obvious to most people but also aren’t too surprising. Foods you may not expect to be UPF include condiments, fruit juices, cereal bars, processed bread, and most yoghurts.

It can be tricky to identify food that has been ultra-processed, especially when the same type of food has been minimally processed, such as bread and yoghurt.

An easy way to identify UPF, especially in the supermarket, is by looking at the ingredient list for items you wouldn’t keep in your kitchen at home. These foods contain chemicals, colourings, sweeteners and preservatives – ingredients you either don’t recognise or only know from supermarket products.

Branding and marketing can also be an easy tip-off. Most unprocessed foods (such as apples, salmon, and milk) aren’t advertised on TV or at bus stops.

The Ultra-Processed Food Panic

While UPF isn’t a brand new phenomenon, it has recently been brought into the spotlight by Dr. Chris van Tulleken’s book: Ultra-Processed People. Alongside a series of articles and documentaries, van Tulleken has embarked on a campaign to make people aware of UPF and the health risks that come with eating it. The sudden influx of media attention has caused many to panic over our UPF-heavy diets.

There are several health risks associated with a high intake of UPF, including a higher likelihood of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cancer. Dr van Tulleken attributes the global obesity crisis to the increased consumption of UPF, due to its higher calorie count, lower nutritional value, and lower cost than processed food. Studies have also found that UPF increases the risk of earlier death by 20 per cent.

“Overall, ‘Ultra-Processed People’ is the best introduction to ultra-processed foods I’ve encountered.” @JerryMande reviews @DoctorChrisVT’s new book. #ProcessedFood #Nutrition https://t.co/ydts4K7JCr

— Harvard Public Health magazine (@PublicHealthMag) September 2, 2023

However, the amount of long-term studies into UPF is lacking, as it has only been part of our diets for approximately half a century. Many of the health risks are still unknown.

Despite the health risks associated with ultra-processed food, only four countries have published national official dietary guidelines regarding it. The UK is not one of them. In 2023, the UK’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) issued a statement, saying there was insufficient evidence to make recommendations about processed foods.

Looking at food in a new way

Nutritional labelling is mandatory in the UK. Every food label contains information about the fat, saturates, sugars, and salt content. We use a ‘traffic light‘ system, so you know whether a food has high, medium, or low amounts of each nutrient.

The government and media also frequently advise us about what we should be eating, using the latest studies on nutrition. The ‘traffic light‘ system makes it easy to follow this guidance.

Traffic light food labeling is a color-coded system that indicates whether a food is high, medium, or low in certain nutrients, making it easier for consumers to make healthier food choices. Green represents low nutrients, amber represents medium, and red represents high. pic.twitter.com/zu0UT8JvSr

— Rhema Ikokwu (@RhemaIkokwu) April 25, 2023

In the early 2010s, we were told that sugar was “the new enemy” in the “war on obesity”. This led to the implementation of “sugar taxes”, increasing the prices of multiple soft drinks to cut down consumption.

Prior to the phobia of sugar, we were frequently advised to eat low-fat, despite there being little evidence of the proposed health benefits. At the same time, the Atkins diet instilled a fear of carbohydrates in the population, with 7% of men and 10% of women trying it out.

Now, Dr. van Tulleken argues this classification is the wrong way to eat.

The Food Standards Agency claims that looking at food in terms of “nutritional value” doesn’t give us the information we need to “make healthy choices”. Dr van Tulleken suggests the level of processing is more important for our health than the type and level of nutrients in our food.

Instead of nutritional labelling, van Tulleken advocates using the NOVA system to classify foods. This would make it easier to reduce the amount of UPF we eat.

The real danger of UPF

“What makes UPF so dangerous is how addictive it is.”

Scientists have attributed overeating and obesity to the increased availability of highly varied, palatable foods. Addiction-like eating behaviour (you might know it as binge eating) is more likely to be triggered by these foods, which are rich in sugar, fat, and salt. You may remember that these are the exact same nutrients commonly added to ultra-processed foods. It isn’t a coincidence. What makes UPF so dangerous is how addictive it is.

In 2019, nutrition researcher Kevin Hall conducted a study intended to demonstrate that the link between UPF and obesity was nothing more than a coincidence. Instead, he proved the opposite. Hall found that eating UPF causes overeating and weight gain, regardless of the sugar content in the food. Blood tests showed that in the bodies of people living on UPF diets, the hormones responsible for hunger remained elevated after eating. No matter how much they ate, they didn’t feel full.

You might have experienced this before if you’ve ever eaten a bowl of cereal and immediately refilled it. Or if you’ve tried to eat recommended portion sizes and found you don’t feel satiated. Because UPF has low nutritional value, it doesn’t fill you up. So, we end up eating large quantities of high-calorie food.

Hankering for more

Food addiction is a common problem, affecting as many as 20% of people.

“It’s unclear whether ultra-processed food causes addictions or simply enables them”

Food can trigger the release of dopamine in mesolimbic regions of the brain. This is the same response we have to taking highly addictive drugs. Within the brain, food can also trigger the same reward systems and activation patterns. To put it in layman’s terms, food can be as addictive as taking heroin or cocaine.

The Yale Food Addiction scale outlines sweets, starches, salty snacks, fatty foods, and sugary drinks as the most addictive foods. They might as well be reading from a UPF shopping list. It’s unclear whether ultra-processed food causes addictions or simply enables them (other factors can play a role, outside of food). But it’s undeniable that the two have become more prevalent at the same rate.

Most of us are addicted to UPF, having been raised on it from birth. Even if you don’t struggle with overeating, the proof of addiction is evident in the fact we continue to crave and buy these foods. Most of us can’t watch TV without reaching for a packet of crisps. There are biscuits in the cupboard to share with guests. Every morning, we crunch through toast or pour a bowl of cereal.

With this in mind, is a future without UPF even possible?

A glimmer of hope

Fortunately, there has been a growing movement to eat fewer chemicals, preservatives, and additives.

In recent years, we’ve seen the introduction of brands that pride themselves on using minimal ingredients, such as BEAR snacks and Eat Real. Cooking videos on TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube inspire people to make their own food, instead of grabbing something pre-prepared from the supermarket. Eco-friendly stores, which allow people to fill their own containers with unprocessed ingredients, are becoming more mainstream as concerns about the climate crisis increase. If you’re interested in cutting down on UPF, there’s plenty of information and resources available that make it possible.

The sheer amount of UPF today (especially if you eat vegan or gluten-free) makes it difficult to avoid it completely. And there’s absolutely no harm in eating processed foods every now and again. It’s convenient, delicious, and poses no risks in small amounts. As with all foods, it’s probably best enjoyed in moderation.

But it’s important to pay attention to what exactly we’re consuming. Think: how much food do you eat in a day that isn’t “real” food?

READ NEXT:

-

IS COOKTOK KILLING THE NEED FOR COOKBOOKS?

-

WHAT IS THE FUTURE OF THE MEAT INDUSTRY?

-

WHAT I EAT IN A DAY: INSPIRING OR HARMFUL?

Featured image courtesy of Franki Chamaki on Unsplash. No changes made to this image. Image license is here.

this was a really interesting read!

Well researched and very informative article.