Amelia Perry

Content warning: this article contains an extensive discussion of disordered eating, restrictive diets and other behaviours widely associated with eating disorders.

I’d like to start with some statistics. It’s estimated that around 1.25 million people in the UK suffer from an eating disorder of some description. 25% of these are male, and about five years ago there was around a 10% annual increase in cases. Anorexia Nervosa has the highest recorded mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder. And the chances of recovery from anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa are just under 50%. It doesn’t take much research to understand just how much of a problem eating disorders are… yet GPs receive less than 2 hours of training on eating disorders throughout their entire medical degree.

I think there’s an assumption that those successfully in recovery from an eating disorder can put the whole thing behind them, and to a certain extent, move on. Most of the time, however, by that point, the damage has already been done. The hidden physiological side effects of eating disorders are a lot of the time, irreversible. In addition to this, there is, of course, a lot of psychological trauma to work through too. This is why TikTok’s glamorisation of eating disorders has to stop – making light of long term damage is never okay.

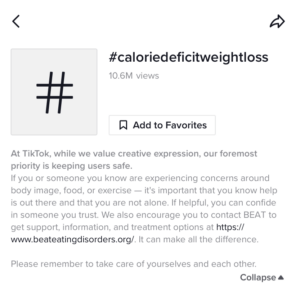

We all know that TikTok tends to promote a certain lifestyle – whether it’s that girl, this girl, being a girl boss, a pick me or an anti-pick me (yes, that’s apparently a thing now), you can pretty much select a personality and shape it around what you see on your For You Page. Those aren’t the videos we need to be worried about. It’s the ones tagged skinnycheck, calorie deficit and wieiad (What I Eat In a Day) that are the real concern. A quick search of some of these tags does now bring up a disclaimer, but this is only something that’s been slowly phased in over the last few months. And is it enough?

Image courtesy of author.

We’ve heard time and time again how dangerous Instagram influencers are, with their pills, shakes and waist trainers trying to sell you that ‘summer body’ (that’s not a thing, by the way), but TikTok is far, far worse for a few reasons. For a start, 60% of the app’s users are between the ages of 16-24 which is widely agreed as being the peak time at which an eating disorder may develop.

It’s the algorithm itself that’s the real issue though. Research has shown it takes less than a day of scrolling, looping and engaging with certain content to alter what’s on your FYP. Take into account the fact that the average user (in the US at least) opens the app a minimum of 8 times a day for at least ten minutes at a time – it’s not hard to see how quickly you can fall down a bit of a wormhole.

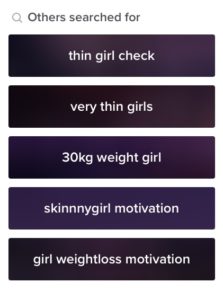

Now, this concept might not be surprising to those who are frequent users of the app – how many times have you ended up on a ‘side’ of TikTok that doesn’t apply to you? Pretty often, I’d wager, but most of the time it’s harmless – whether it’s Crunchy Moms, Ex-Mormons, or a healthy dose of ShrekTok, it can often be an interesting insight into a different, previously unconsidered perspective. The point stands though, consuming these videos isn’t doing anyone any damage, at all. Despite their protestations that videos are monitored by both human and AI checks, TikTok is still enabling these wormholes. A quick, even innocuous, search not only brings up video after video but search suggestions too.

Image courtesy of author.

I mean, really?

I’ve seen more than a few fully grown adults promoting eating just enough to meet the basic nutritional needs of a four-year-old human being.

As many people who’ve recovered from an eating disorder will tell you, they are an incredibly slippery slope. What might start as a well-intentioned weight loss journey can very quickly spiral out of control. It’s the same on TikTok. A few weight loss videos here and there, and before you know it your entire FYP is filled with ‘thinspo’, unsustainable habits, and diets containing the calorific intake of a toddler. Sadly, though it might sound like it, that’s not an exaggeration. I’ve seen more than a few fully grown adults promoting eating just enough to meet the basic nutritional needs of a four-year-old human being.

This is not to say that TikTok should not be a place for fitness creators, quite the opposite. There’s a super supportive community on the app, sharing tips, motivation and gym how-tos. Nearly all of these TikTokers start with a disclaimer that what may work for them might not work for you, and that being healthy and happy will always be more important than looking a certain way. The same is not true of everyone, however, and those bragging about their unhealthy habits seem to be the ones who are trending, making their way onto the feeds of so many impressionable (young) people.

Once you are trapped in this cycle, it’s nearly impossible to find your way out, and it’s even harder to remind yourself that those videos can be so easily edited – just because it might look like they’re getting the precise results they want, remove the filters and convenient posing and those abs probably look a little less defined. Not to mention, any ‘influencer’ advocating for these habits is pretty conveniently going to omit how sluggish, hungry and downright crappy they are probably feeling.

Sadly, it often goes further than promoting weight loss. I’ve seen tips on how to hide eating disorders from parents, how to suppress your appetite and different methods for purging. Content that is positively pro-eating disorder is where we absolutely have to draw the line. Despite the fact there’s a whole hoard of influencers doing their best to negate this ED culture that TikTok has fostered, and an entire subgenre of creators in recovery working to dispel the myth that eating disorders are glamorous and desirable, it’s just not enough.

Developers at TikTok need to be doing more to address the issue, remove these harmful tags and suspend creators in violation of their terms. It goes without saying that current sufferers need to be treated and helped, but there is so much more that we can do to prevent more cases from developing, and making social media a safer, more body-positive environment seems like a good place to start.

Featured image courtesy of Eyestetix Studio via Unsplash. Image license can be found here. No alterations made.

1 Comment